Ecole d’Horlogerie Le Locle observatory chronometer pocket watch and wristwatch full set

- Posted on

- By Wouter van Wijk

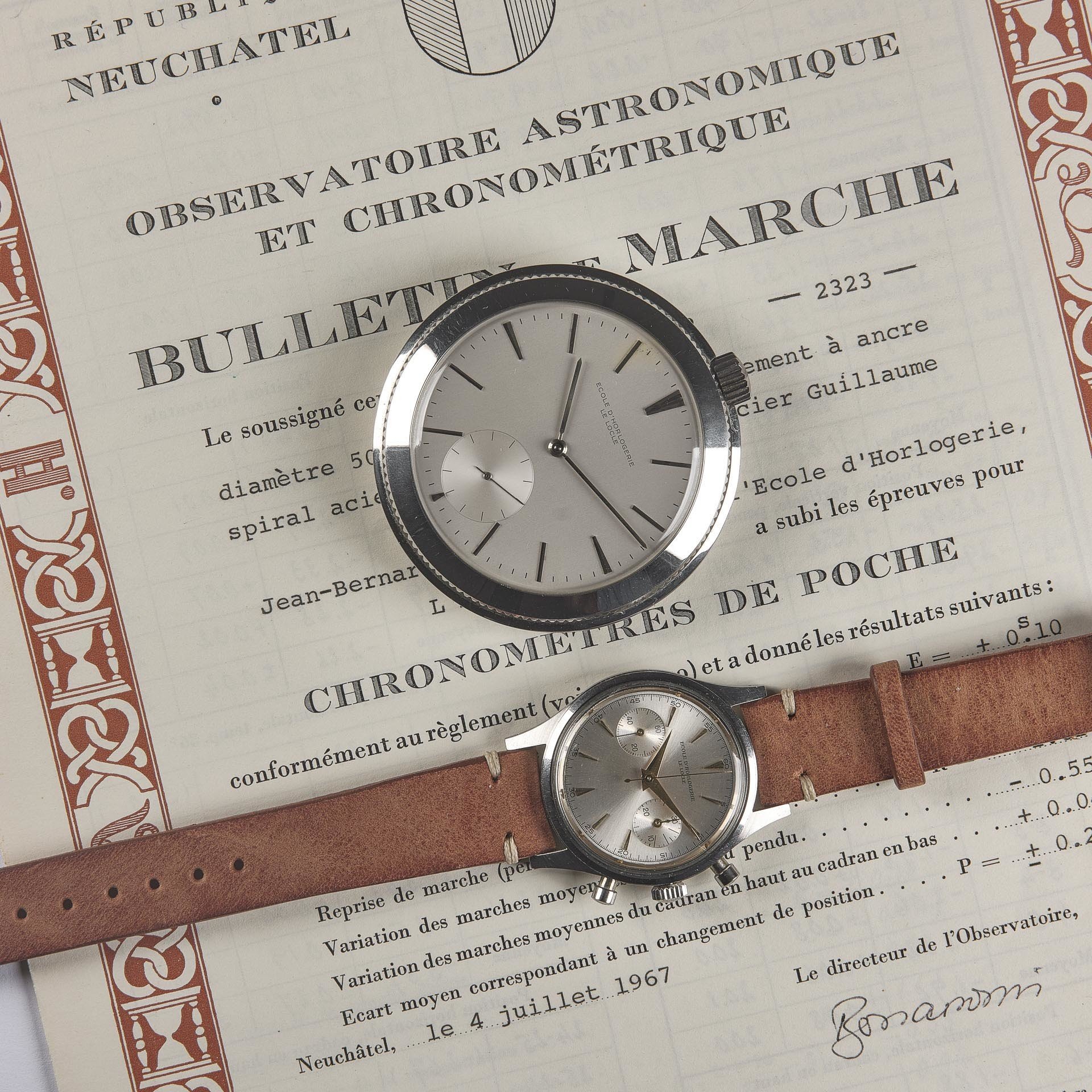

WRIST ICONS is offering a graduation masterpiece set consisting of a pocket watch and wristwatch chronograph. The pocket watch was tested at the Neuchâtel Observatory. The chronograph underwent chronometer testing at the "BO" (Bureaux officiels) in Le Locle. The watches come as a full set with all the documents possible. This is the first time such a complete set has been available to the open market and it has been preserved as a time capsule, as an untouched time keeping heirloom from a bygone era.

Ecole d’Horlogerie Le Locle observatory chronometer pocket watch and wristwatch chronometer chronograph full set

WRIST ICONS is offering a graduation masterpiece set consisting of a pocket watch and wristwatch chronograph. The pocket watch was tested at the Neuchâtel Observatory. The chronograph underwent chronometer testing at the "BO" (Bureaux officiels) in Le Locle. The watches come as a full set with all the documents possible. This is the first time such a complete set has been available to the open market and it has been preserved as a time capsule, as an untouched time keeping heirloom from a bygone era.

“WRIST ICONS brings you a masterpiece. Literally.”

These school watches (montre-école) belonged to an alumnus of the prestigious Technicum watchmaking school in Le Locle, Switzerland. That particular student was one of the few selected high-flyers who graduated in 1967 as a technical engineer. “Ingénieur-Technicien” was the highest possible education-track at the Technicum (5 ½ years including thesis - equivalent to an university degree in Microengineering in 2020).

WRISTWATCH

You are looking at the largest known version of any school watch for the wrist (pre 1970) – measuring a contemporary 37mm in Ø. Executed in steel, the case is a rare “pop-out” waterproof clamshell type (also referred to as “monocoque” case), which was patented by the casemaker Schmitz Frères & Co (Brevet 189190) in 1937. The Valjoux 23 received the uttermost attention in terms of hand-finishing. The hand-finishing of the movement components included the application of Côtes de Genève, perlage, anglage and black polishing. Beside the undeniable beauty the chronograph packs some serious chronometric performance. Attested by the “Class 1” chronometer certificate with “especially good results”. The chronograph underwent chronometer testing at the "BO" (Bureaux officiels) in Le Locle. Every major Swiss village with ties to the watch industry had a BO. In 1973 all the BOs were merged in the central testing organization called COSC.

The wristwatch comes with the following box and papers:

1 - Orig. chronometer bulletin from the Bureaux officiels in Le Locle with “especially good results" distinction (see upper right corner).

2 - Supplementary document with rate data, highlighting the “Class 1” predicate (passed with distinction).

3 - Orig. box containing the accompanying “small” chronometer certificate (also stamped with “especially good results”).

4 - School document certifying that the watch was handed back (after testing) to the student in 1967.

POCKET WATCH

The pocket watch is an extremely rare full-fledged observatory chronometer which was tested at the prestigious Neuchatel observatory and scored a remarkable high mark (N-score=6,87). Less than 40 pieces have been submitted to the observatory of that particular variant of the 50A. Like the chronograph, the pocket watch retains its original box, original Bulletin de March, prize certificate and an additional document from the school.

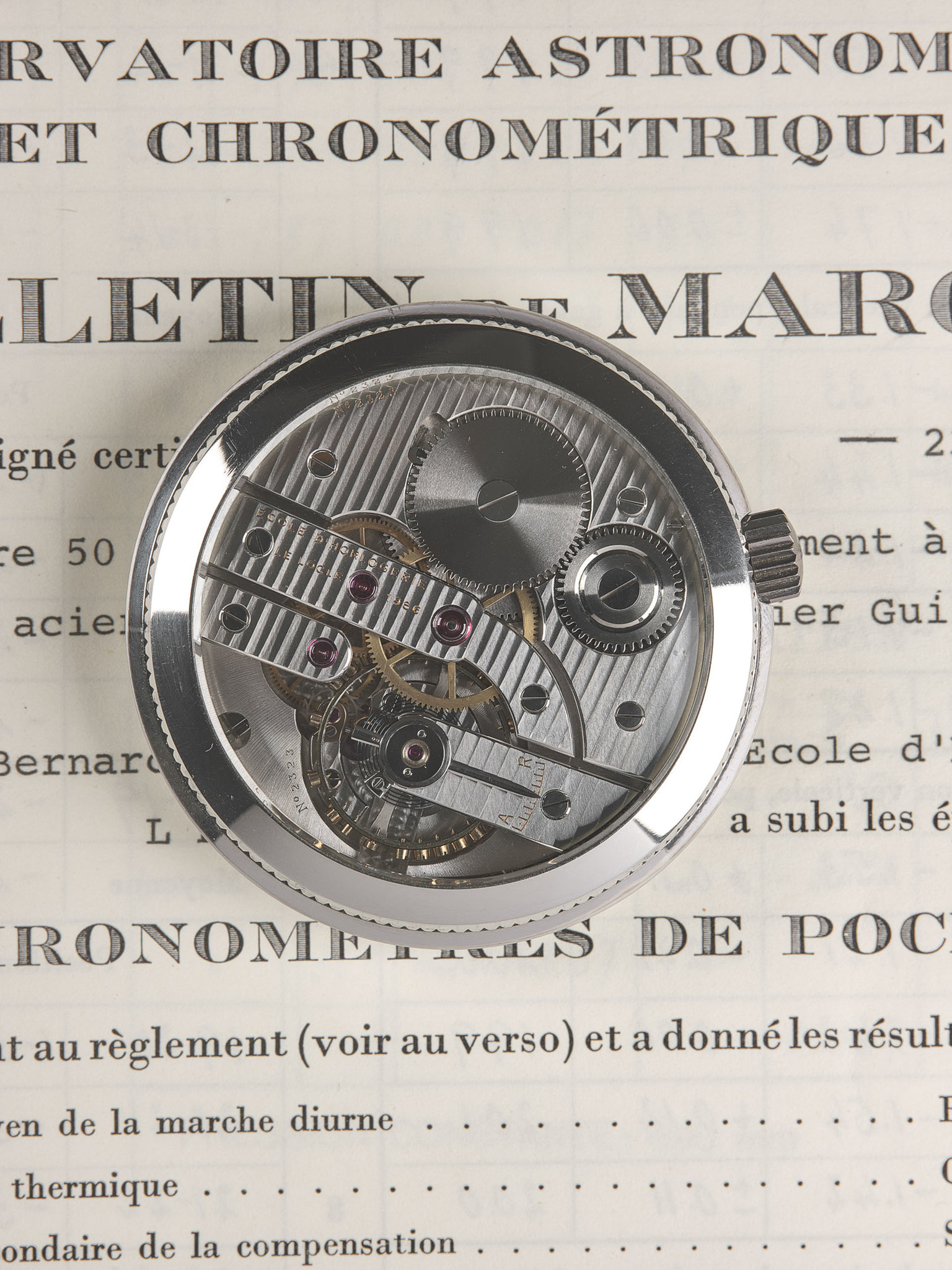

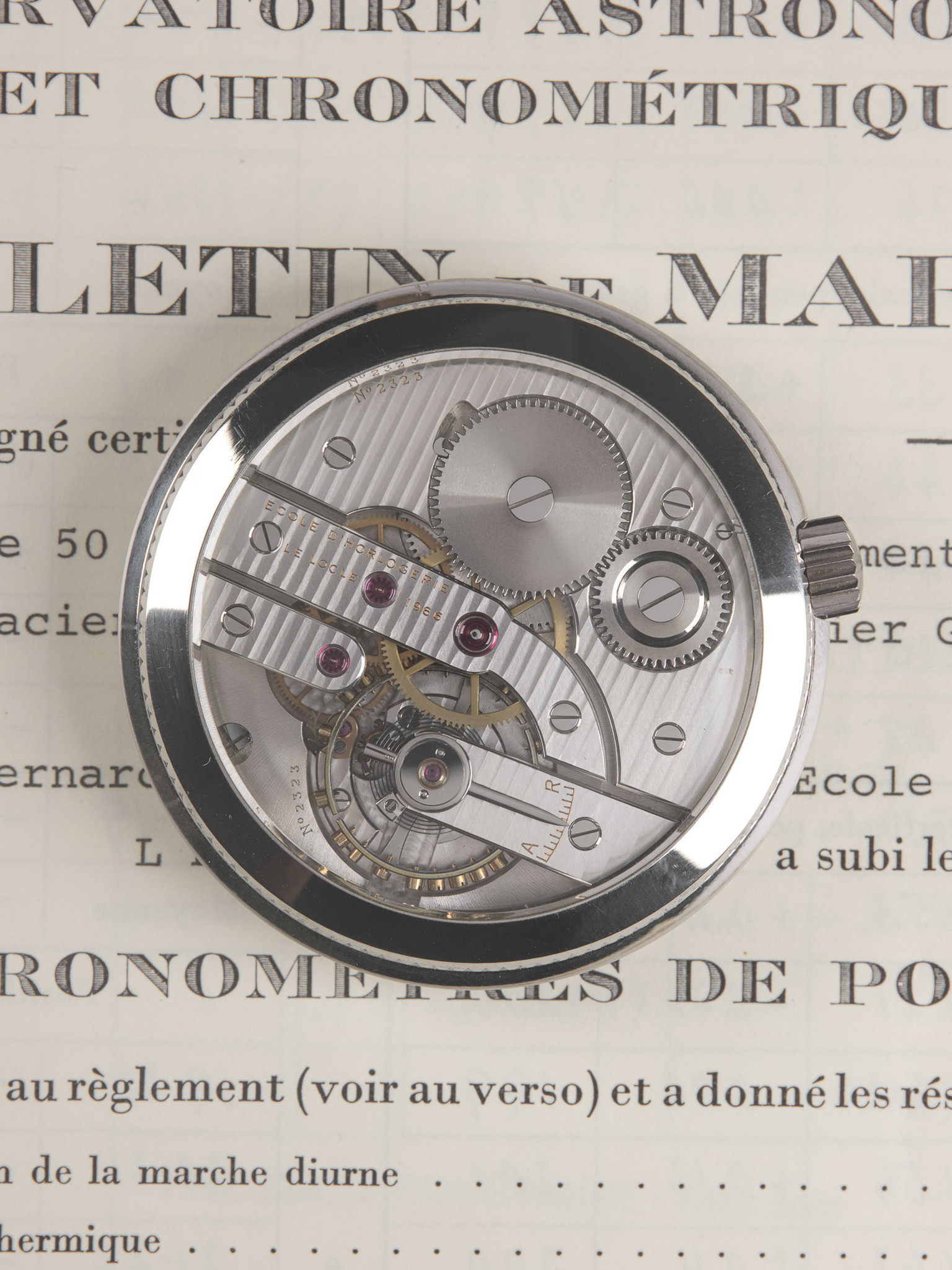

The caliber is called the “50A” and classified among scholars as the so called "3rd version". The caliber 50A is considered without a doubt as the absolute pinnacle in precision timekeeping and finishing and is one of the most sought after pieces from any of the ten Swiss watchmaking schools.

Executed in steel, the fluted Breguet styled case was one of the few components which was sourced externally by the watchmaking school and not handmade by the students. The Caliber 50A was fully developed in-school. In comparison, most other watchmaking schools used ébauche calibers from known Swiss watch manufacturers (like Zenith, IWC or JLC). Hence, the cal. 50A was always made completely from scratch by the respective student. The movement is mainly made from German silver (aka Maillechort). The bridges are plated and decorated with a wonderfully fine Côtes de Genève. The hand-finishing of the movement components included perlage, anglage and black polishing. The movement is just stunning and visible through the glass opening on the back.

Find below what “full set” means in the world of school watches:

1 - Original Neuchâtel Observatory “Bulletin de marche”

2 - Original box

3 - School document certifying that the watch was handed back (after testing) to the student in 1967.

4 - Prize awarded by the Conseil d’Etat de la République et canton de Neuchâtel

History of the marine chronometer

Nowadays we can rely on our iPhone or smartwatch for accurate time keeping. But in the early days of timekeeping it was crucial to measure time as accurately as possible. Timekeeping was especially vital at wartime. If you would sail a ship you could navigate by longitude using a marine chronometer as introduced by John Harrison in 1730 and a sextant. The angle between the sea horizon and the celestial body is measured with a sextant and the time noted. If the time wasn’t accurate you could be calculating your destination by miles apart and as a consequence lose a battle.

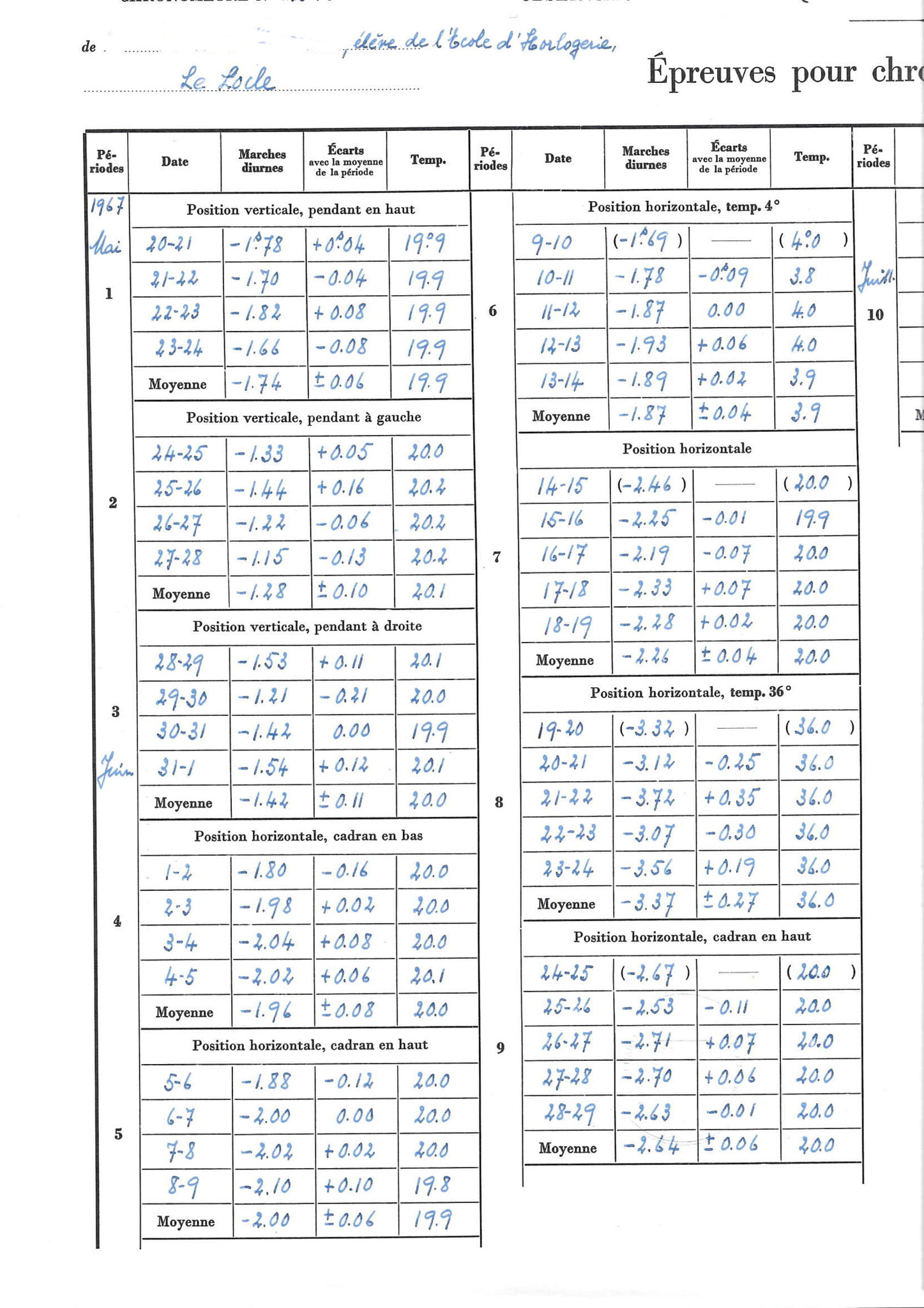

History of the observatory chronometer and timekeeping competitions

With the rise of the marine chronometers during the late 18th and 19th century there also became a need to measure the accuracy of these chronometers. At the same time there were big developments in the world of optics. Now the optical techniques could be used to measure the theories once developed by astronomers and mathematicians such as Christiaan Huygens, Johannes Kepler, Tyco Brahe, and Sir Isaac Newton. From the necessity for accurate timekeeping measurement, various astronomical observatories developed an accuracy testing regime. In Europe, the Neuchâtel Observatory, Geneva Observatory, Besancon Observatory and Kew Observatory were examples of prominent observatories that tested timepiece movements for accuracy. The testing process lasted for many days, typically 45 days. Each movement was tested in 5 positions and 2 temperatures, in 10 series of 4 or 5 days each.

There was a golden age of real watchmaking that lasted from the 1870s to the 1970s when the performance of a watch was closely correlated with its value and price. In the newly industrialized world of trains and the telegraph, and until well into the 20th century, if you travelled, managed a business or a factory, held public office, or speculated on the stock market, a trustworthy watch was as essential as the cellphone is today.

The competition at the Neuchâtel Observatory started already in 1860. Widespread attention (public awareness) of the competitions was at its peak in the 1960s - 100 years later. The most stringent and demanding chronometric testing was done at the observatories. While most chronometer wrist watches received their chronometer certificates from the less demanding BO/COSC (see above). Further, several manufacturers like Omega and Ulysse Nardin used in-house testing to issue Bulletins for their Chronometer watches.

The Geneva Observatory was only open to brands based in the canton of Geneva. Geneva-based brands like Patek Philippe and Rolex, primarily submitted their watches to the Geneva Observatory for testing, though Omega also competed in Geneva.

The most prestigious observatory in Europe was certainly the Neuchâtel Observatory. The precision regleurs appreciated and prefered the meticulously controlled testing environment (e.g. air pressure and humidity) in Neuchâtel as told by Dr. Christian Müller, the creator of the Observatory Chronometer Database (OCD) who spoke with one of the former Omega regleurs. For instance, Neucahtel had a hermetically sealed double door system for entering the testing room. Which was not the case in Geneva. The movements that passed were issued a certification—a “Bulletin de Marche”—elevating their status to officially certified Observatory Chronometers.

The testing process lasted for days (typically 45 days). Each movement was tested in 5 positions and at 2 temperatures, in 10 series of 4 or 5 days each. The tolerances for error were much stricter than the BO/COSC standard. The Bulletin de Marche from the observatory stated the testing criteria on the back while you will find calculated overall results in the front and the detailed rate data (during the testing periods and different conditions) inside the Bulletin. A movement with a Bulletin de Marche from an observatory became known as an Observatory Chronometer. If the movement passed the test, the manufacturer assigned movement number became the "chronometer number" which links the movement to its Bulletin.

Applicable to then Observatory of Neuchâtel and after the year of 1953, there were 4 categories:

- Marine chronometer

- Chronometer de bord

- Chronometre de poche (pocket watches)

- Chronometer de bracelet (wristwatches limited to 30mm in diameter or 707mm2 surface)

Besides traditional watch manufacturers, also the highly specialized supplier industry, which consisted of manufacturers of parts, lubricants and raw materials, used the competitions to test new materials and their technical developments. The companies Société des Fabriques de Spiraux Réunies and Fabrique de Nivarox S.A. were at the frontline in escapement technology and sponsors of the prestigious guillaume prizes of the competitions that were awarded to precision regleurs. The continuous commitment of these two companies goes back to the early 1960s. Various combinations of spirals (Isoval, Nivarox) and balance wheels (Guillaume, Glucydur and Nickel) were tested at the observatory competitions. There was a stiff competition between these two companies, since both wanted to push their own hairsping and balance wheel technology on the market.

History of the school watch

During the 20th century the most well-known Swiss watch schools were the Ecole technique de la Vallée de Joux, the Ecole d’horlogerie de Porrentruy, the Ecole d’Horlogerie de St-Imier, the Technicum Le Locle, the Ecole d’horlogerie de Genève, the Technicum cantonal Bienne and the Technicum La-Chaux-de-Fonds. Until the late 1960s students had to build their own graduation piece to complete their education. School Watches (called montre-école or Pièce École) are by definition graduation pieces that showcase the skills of the watchmaker after completing their education.

These watches are very interesting since they show a level of finishing and precision that’s even surpassing the best examples from the top tier brands. Due to the fact that these watches are pretty unknown to the average watch collector, one can pick up these pieces quite affordable.

In the beginning mainly pocket watches, however, also larger pendulum watches and demonstration pieces have been created as graduation masterpieces. These pocket watches were designed and built completely from scratch by the students. Be it melting metal, crafting the components or finishing the movement as well as the case by hand. Raw components were purchased from Swiss manufactures and modified in the school by the student with the available tools and machines.

In the late 20th century it became more common at most of the watchmaking schools to buy ébauche movements (raw unfinished or fully finished movements) and prefabricated cases, dials, hands and other furniture from renowned brands such as IWC, Zenith or Heuer.

The most demanding education track at the watchmaking schools in La Chaux-de-Fonds and Le Locle was the Technicien-horloger (Technical watchmaker). In small groups and under the guidance of the best teachers, the elite of the Swiss watchmaking industry was born. Four years of painstaking construction plus one year of fine-adjustment culminated in the submission of the finished graduation piece (pocket watch) to the observatory competition in Neuchâtel – putting the acquired skills of the freshly minted watchmakers to the test.

From 1923 to 1976 the watchmaking schools Le Locle and La Chaux de Fonds dominated in terms of the total number of submissions to the observatory in Neuchatel (Combined, these two schools represented 90% of all submission from all of the Swiss watchmaking schools). The calibers submitted to the observatory by the watchmaking school in La Chaux-de-Fonds were the fully in-school developed Calibre D (50mm) and the legendary 65 mm. Later in 1963 until 1976 the often mythically described calibre 49.9 was fetching prizes and fabulous N-scores at the chronometry competitions in Neuchâtel. The 49.9 was the last true in-school developed and built caliber in La Chaux de Fonds and stands as the final culmination of almost 100 years of precision watchmaking expertise at the watchmaking school in La Chaux de Fonds.

The 50 mm caliber (named cal. 50A) of the Technicum in Le Locle

The Technicien-horloger (see above) track was introduced in 1895 by Paul Berner (Director of the watchmaking school in La Chaux- de-Fonds) and was quickly adopted in the beginning 20th century by the watchmaking school in Le Locle. The creation of the cal. 50A was exclusively reserved (with some exceptions) for the few students who trained on the technicien-horloger track.

The cal. 50A caliber is bar none the most impressive school watch from Le Locle. The caliber has a balance wheel that almost measures 50% of the full diameter of the movement. This was achieved by lowering the escapement wheel bridge under the balance wheel (similar to Omega 60.8, Peseux 260 or cal. 49.9 from watchmaking school in La Chaux de Fonds). Further increasing the balance wheel diameter (over 50% of the total movement diameter) would require offsetting the the center wheel (seen on the cal. 135 from Zenith) or constructing a round off-center movement (Longines 30B). Historically chronometers were designed with oversized balance wheels. The idea was to increase the mass/diameter of the balance wheel in order to achieve a higher moment of inertia of the oscillating balance wheel. This resulted in better rate stability, since the oscillation frequency of the balance wheel is less susceptible to alteration by external influences. According to the available scholarship, there are 3 distinct versions of the caliber 50A. The first version was almost exclusively equipped with a detent escapement, the second version saw detent and anchor escapements while the third version is known to have been built only with the traditional anchor escapement. The three identified distinct versions of the cal. 50A differ in minor changes in the overall construction of the movement (eg.: click design etc.) It should be highlighted that a particular movement of the third version of the 50A, as being sold here, holds the absolute precision record for any schoolwatch which was ever submitted to any of the Swiss observatories (N=2,82). Cementing the chronometric prowess of the caliber 50A in horological history.

The caliber 50A features a Guillaume balance wheel (GBW). Why is it so special? Charles Édouard Guillaume won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1920 in recognition of the service he had rendered to precision measurements in physics by his discovery of anomalies in nickel steel alloys. The GBW saw widespread adoption by chronometer manufacturers who submitted pieces to the observatory competitions. The GWS is a split bi-metallic balance wheel made of anibal-brass and had superior temperature compensation compared to the older bi-metallic compensating balance wheels which were made of steel-brass. The GBW was a big step forward in the accuracy of mechanical timekeeping and became the de-facto standard for observatory chronometers until the end of the competitions, even long after monometallic balances became available.

Condition⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀⠀

This particular pocket and wristwatch have been kept all original. We picked it up from a collector who bought it directly from the student who graduated with these pieces. It is upon the new owner to service the watch. The watch runs and keeps time. The chronograph functions work flawlessly. There is a minor spot on the dial of the pocket watch at 11.

Out of respect for the privacy of the watchmaker, we have made his name invisible on all documents but also on the timepiece. His name is engraved on the pocket watch.

As with all of our pre-owned watches this watch comes with a full 12 month WRIST ICONS warranty that will be invoked from the day of purchase. Please check our website to have a look at the high resolution pictures on a macro level. You will see every detail at its best.

| Brand | Ecole d’Horlogerie Le Locle |

| Model | Observatory chronometer pocket watch |

| Reference | Caliber 50A 3rd version |

| Gender | uni-sex |

| Year | 1967 |

| Material | stainless steel |

| Dimensions | movement 50 mm |

| Dial | silver, signed Ecole d’Horlogerie Le Locle |

| Watch Movement | manual winding |

| Bracelet/Strap | none |

| Box/Paper | box and papers |

| Condition | excellent |

| Brand | Ecole d’Horlogerie Le Locle |

| Model | chronometer chronograph wristwatch |

| Reference | Valjoux 23 |

| Gender | uni-sex |

| Year | 1967 |

| Case | stainless steel case. Executed in steel, the case is a rare “pop-out” waterproof clamshell type (also referred to as “monocoque” case), which was patented by the casemaker Schmitz Frères & Co (Brevet 189190) in 1937 |

| Material | stainless steel |

| Dimensions | 38 mm |

| Dial | classic silver dial signed Ecole d’Horlogerie Le Locle, two-register with beautiful arrow shaped golden hour markers with really big shiny golden dauphine hands. |

| Watch Movement | manual winding |

| Bracelet/Strap | WRIST ICONS leather strap made by Jean Paul Menicucci |

| Box/Paper | box and papers |

| Condition | excellent |

Sources:

- Caliber 50A, Klassik Uhren Magazine 3/2016

- Dix écoles d'horlogerie suisses By E. Fallet and A. Simonin

- Marine Chronometer Its History and Developments Rupert T. Gould

- https://wornandwound.com/history-of-chronometers-pt-1-origins/

- https://wornandwound.com/history-of-chronometers-pt-2-observatory-trials/

- https://monochrome-watches.com/the-race-for-accuracy-the-definition-of-a-chronometer/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Observatory_chronometer

- http://www.observatory.watch/

- https://longines30l.com/wordpress/?page_id=690

- https://watchesbysjx.com/2018/09/when-accuracy-mattered-part-one-watchmaking-heroes-and-the-battle-for-time.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Édouard_Guillaume

- https://magazine.bulangandsons.com/school-watch-chronograph